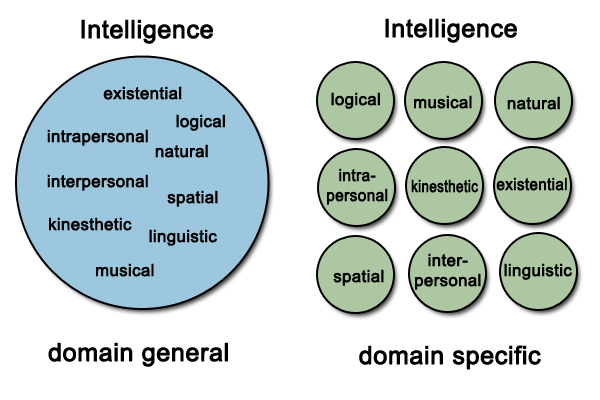

Intelligence theories fall into two categories: the domain-specific believe that intelligence is made up of multiple abilities and skills. The domain-general believe that intelligence is a single general ability.

Cognition

PSYC 1301

Cognition is the process of thinking, problem solving, and decision-making. Language, imagery, reflection, conceptualization, evaluation, and insight make up thinking. Cognitive psychology is the science of how people think, learn, remember, and perceive. In the previous sessions, we learned about the processing, storage, and retrieval of information to and from memory and expression through language and thought. The textbook states that many people consider intelligence the primary trait that sets humans apart from animals. Others will say emotion, still others will say language sets us apart. Those who consider intelligence to to be the primary trait point out that abstract reasoning is found only in humans.

|

Click here to view the video clip "What is Intelligence?"

|

We consider intelligence to be of primary importance; however, we do not always agree on the definition of intelligence. For many years, we considered a person intelligent if he or she did well on standardized IQ tests and academics. But standardized tests do not take cultural and social factors into account. Although standardized tests are still used today, they are used with reservation and other factors are considered as well. The textbook defines intelligence as a set of cognitive skills that include abstract thinking, reasoning, problem solving, and the ability to acquire knowledge. Others would add mathematical ability, general knowledge, and creativity to the definition. Regardless of the factors considered, contemporary experts agree that the best definition of intelligence should include abstract reasoning. |

|

|

Intelligence theories fall into two categories: the domain-specific believe that intelligence is made up of multiple abilities and skills. The domain-general believe that intelligence is a single general ability.

|

Theories of intelligence start emerging in the early twentieth century. Early theorists disagreed on the question of intelligence as a single factor or multiple components.

Intelligence as One General Ability

Charles Spearman believed that intelligence is general. People who are bright in one area are bright in other areas as well. Spearman came to this conclusion based on research that consistently showed that specific dimensions or factors of intelligence were all measuring pretty much the same thing. Thus, Spearman's "g" factor theory describes intelligence as a single general factor made up of specific dimensions. The three dimensions that are correlated are verbal, spatial, and quantitative intelligence. Verbal intelligence is the ability to solve problems and analyze information using language-based reasoning. Quantitative intelligence is the ability to reason and solve problems by carrying our mathematical operations and using logic. Spatial intelligence describes the ability or mental skill to solve spatial problems such as navigating, and visualizing objects from different angles. His theory was criticized early on because intelligence tests do not measure all aspects of what it means to be intelligent.

Intelligence as Multiple Abilities

Theorists in the Intelligence-as-Multiple-Abilities camp believe that IQ test scores should not be used as the only measurement of intelligence. They believe that other important aspects of intelligence are not measured by IQ tests. Therefore, the multiple-factor theory of intelligence states that different aspects of intelligence are distinct enough that multiple abilities must be considered. L.L. Thurstone, Director of the Psychometric Laboratory and President of the American Psychological Association (1933) believed that intelligence encompasses seven mental abilities that are relatively independent of one another: verbal comprehension, word fluency, number facility, spatial visualization, associative memory, perceptual speed, and reasoning. For an overview of Thurstone's work, go to http://www.intelltheory.com/lthurstone.shtml.

In contrast, American psychologist Raymond Cattell divided mental abilities into two clusters. The first is crystallized intelligence, or abilities such as reasoning and the verbal and numerical skills that are accumulated from education and experience. The second is fluid intelligence, or skills such as spatial and visual imagery, the ability to notice visual details, and rote memory. Fluid intelligence or raw mental ability is considered culture free.

John Carroll extended Cattell's model into a hierarchy of three levels of intelligence: general intelligence which is similar to Spearman's g factor, broad intelligence, and narrow intelligence. Both crystallized intelligence and fluid intelligence as well as memory, learning, and processing speed are considered broad intelligence. Narrow intelligence, on the other hand, consists of approximately 70 distinct abilities such as speed of reasoning, general sequential reasoning for fluid intelligence and reading, spelling, and language comprehension for crystallized intelligence.

Becasue the model includes Cattell and Horn's crystalized and fluid intelligences, it has become known as the Cattell-Horn-Carroll model of intelligence.

|

Click here for a visual explanation of Sternberg's triarchic theory of intelligence. |

In the mid-1980s, Yale psychologist Robert Sternberg proposed a triarchic theory of intelligence that includes a much broader range of skills and abilities. He refers to these skills and abilities as successful intelligence or elements needed to succeed in life. According to this theory, intelligence consists of three overarching aspects. Analytic intelligence involves judging, evaluating, or comparing and contrasting information such as IQ tests. Practical intelligence is the ability to solve problems of everyday life and creative intelligence involves solving novel problems and coming up with novel solutions to problems. Intelligent people, according to Sternberg, are adept at making the most of their strengths and compensating for their weaknesses. |

|

|

Psychologist Howard Gardner of Harvard University has suggested that we have multiple intelligences, each relatively independent of others. Specifically, he considers intelligence to include eight distinct capacities or spheres. Gardner suggests that these separate intelligences do not operate in isolation. Normally, any activity encompasses several kinds of intelligence working together. Gardner's model has led to a number of advances in our understanding of the nature of intelligence. The eight intelligences identified by Gardner include linguistic intelligence, mathematical-logical intelligence, spatial intelligence, bodily-kinesthetic intelligence, musical intelligence, interpersonal intelligence, intrapersonal intelligence, and naturalistic intelligence.

|

|

Critics of Gardner's multiple intelligence theory argue that there is not a lot of empirical research testing Gardner's theory. Educators, on the other hand, believe that Gardner's theory addresses the fact that different students learn in different ways and that some students demonstrate ability to perform well in some areas even though they do poorly on IQ tests. |

For an interview with Gardner explaining his theory in his own words, click here. |

Formal theories of intelligence serve as the foundation for the design and administration of intelligence tests. Intelligence tests are designed to measure a person's mental abilities. These tests were first designed to address clinical concerns and followed a simple premise: if performance on certain tasks or test items improved with age, then performance could be used to distinguish more intelligent people from less intelligent people within a particular age group. Using this principle, psychologist Alfred Binet (1857-1911) was asked by the French government to construct a scale for identifying the dullest students in the Paris school system who would benefit by extra help in school. In response, Binet and Theodore Simon developed the first intelligence test.

The Binet-Simon Scale was originally issued in 1908. It consisted of 30 tests arranged in order of increasing difficulty. From the average scores of children, Binet developed the concept of mental age. On this test, children were assigned a score that corresponded to their mental age, which was the average of children taking the test who achieved the same score. Assigning a mental age to students provided an indication of whether or not they were performing at the same level as their peers. It did not allow for comparisons among students of different chronological or physical ages. This test would be translated into English by H. H. Gadded (1866-1957) and then modified by Lewis Terman to "measure" the intelligence of every person, whether mentally disabled or not.

The best-known Binet adaptation, created by Stanford University's L. M. Terman in 1916, is the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale. Terman introduced the term intelligence quotient (IQ), which is a numerical value given to scores on an intelligence test (a score of 100 corresponds to average intelligence). To calculate an IQ score, the following formula was used: IQ score = Mental age/chronological age multiplied by 100 (MA/CA x 100).

The Stanford-Binet is designed to measure skills in four areas: verbal reasoning, abstract/visual reasoning, quantitative reasoning, and short-term memory. Tests are grouped into age levels ranging from age two to superior adult. The examiner starts at a level slightly below the expected mental age and either works up or adjusts downward. The basal age is the level at which all tests are passed and the ceiling age is the level at which all tests are failed.

The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition, Revised (WAIS-IIIR) was developed by David Wechsler especially for adults. The test measures both verbal and performance abilities. The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IIIR) is the most current Wechsler test for adults. All items of a type are grouped into subtests and arranged in order of increasing difficulty. Verbal, performance, and full scale IQ are determined by the use of separate standardized tables for seven age groups from 16 to 74 years of age.

Wechsler also created the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Third Edition (WISC-III), which was meant to be used with school-aged children. It was revised in 1991 and is used for ages 6-16 years 11 months 30 days. Currently it is the most widely administered IQ test for children in the United States. It measures verbal and performance abilities separately, though it also yields an overall IQ score. The "baby" of the Wechsler series for children is the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI) for children ages three to seven years.

Some intelligence tests may discriminate against members of certain cultural or ethnic groups. Culture bias enters testing design when tests reflect subject matter that is primarily known to white middle-class adults or children, and when the tests rely on verbal items. Examples of culturally-biased tests could be paper/pencil, those requiring reading or written responses, speed tests, verbal content tests, tests of recall of past-learned information. Examples of culturally-reduced tests are performance tests, pictorial tests, oral responses, nonverbal content tests, and solving novel problems tests. The Seguin Form Board, the Porteus Maze, and the Bayley Scale of Infant Development are performance tests. The Goodenough-Harris Drawing Test and the Progressive Matrices are examples of culture-fair tests.

For the first 50 years in which IQ tests were given, intelligence was assumed to be a single quality. Test developers ignored research findings on the developmental changes in different aspects of intelligence. These tests also ignored Jean Piaget's view that cognitive abilities of young children are fundamentally different from that of adolescents and that cognitive development occurs in stages rather than gradually over time. In addition, they ignored advances in neuroscience and learning style differences. Nadeen and Alan Kaufman developed the Kaufman-Assessment Battery for Children, or K-ABC as an alternative to the Stanford-Binet and Wechsler tests. This test was the first IQ test to be guided by theories of intelligence. It was designed to measure several distinct aspects of intelligence as well as different types of learning styles. It included different kinds of problems for different ages as well as varied levels of difficulty. The K-ABC has become one of the more widely used IQ tests.

Psychologists use reliability and validity as measures of a test's quality, and for purposes of comparing different tests.

Reliability

Reliability means consistency or accuracy. Reliability is the ability of a test to produce consistent and stable scores. The simplest way to determine a test's reliability is to give the test to a group and then, after a short time, give it again to the same group. If the group scores the same each time, the test is reliable. The problem with this way of determining reliability is that the group may have remembered the answers from the first testing. One method of eliminating this problem is to divide the test into two parts and check the consistency of people's scores on both parts. If the scores generally agree, the test is said to have split-half reliability. Psychologists express reliability in terms of correlation coefficients, the statistical measure of the degree of linear association between two variables. Correlation coefficients can vary from -1.0 to +1.0. The reliability of intelligence tests is about .90; that is, scores remain fairly stable across repeated testing.

Validity

Validity is the ability of a test to measure what it has been designed to measure. Construct validity is the degree to which a test measures the concept it claims to measure. Predictive validity is the degree to which a construct is related positively to real-world outcomes. In general, most intelligence tests assess many of the abilities considered to be components of intelligence: concentration, planning, memory, language comprehension, and writing. However, a single test may not cover all the areas of intelligence, and tests differ in their emphasis on the abilities they do measure.

Criterion-related validity refers to the relationship between test scores and independent measures of whatever the test is designed to measure. In the case of intelligence, the most common independent measure is academic achievement. Despite their differences in surface content, most intelligence tests are good predictors of academic success. Based on this criterion, these tests seem to have adequate criterion-related validity.

Tests must be both reliable and valid.

Test-retest reliability is the consistency of scores on a test over time.

Internal reliability describes intelligence tests in which questions on a subtest correlate very highly with other items on the subtest.

Much of the criticism of intelligence tests has focused on their content. Critics point out that most intelligence tests are concerned with only a narrow set of skills and may, in fact, measure nothing more than the ability to take tests. Critics also maintain that the content and administration of IQ tests are shaped by the values of Western middle-class society and that, as a result, they may discriminate against minorities. IQ tests are also criticized because the results are often used to label some students as slow learners. Finally, IQ tests do not offer information on motivation, emotion, attitudes, and other similar factors that may have a strong bearing on a person's success in school and in life.

Other critics hold that intelligence is far too complex to be precisely measured by tests. IQ tests are also criticized for neglecting to account for social influences on a person's performance. According to recent reviews of the evidence, intelligence tests are good predictors of success on the job. However, because so many variables figure in occupational success, psychologists continue to debate this issue. Robert Sternberg and Richard Wagner have called for a test to be developed specifically to measure skills related to job performance. They refer to the knowledge that people need to perform their jobs effectively as tacit knowledge.

Convergent thinking problems are those problems that have known solutions that can be reached by narrowing down the possible answers, whereas divergent thiking problems have many possible solutions. Some solutions work; some do not.

Solution Strategies

An algorithm is a prescribed method of problem solving that guarantees a correct solution if the method suits the problem and if it is carried out properly. Solving a mathematical problem by use of a formula is an example of the use of an algorithm.

Insight solutions or Eureka insights occur when a sudden solution comes to mind - that "a-ha" idea.

Thinking-outside-the-box occurs when a person does not follow strict self-imposed constraints and looks at a problem differently.

Heuristics are rules of thumb that help to simplify and solve problems, though they do not guarantee a correct solution. Many types of heuristics are in use. We use the representative heuristic to estimate the probability of one event based on how typical it is of another event. We use the availability heuristic to make decisions based on the ease with which estimates come to mind or how available they are to our awareness.

Problem representation, defining or interpreting the problem, is the first step in problem solving. We decide what the problem is and what steps we are going to use to solve the problem. Expertise in a field increases a person's ability to interpret a particular problem.

Trial and error is a problem-solving strategy based on the successive elimination of incorrect solutions until the correct one is found. But trial and error is time-consuming, and a hit-or-miss approach.

Hill climbing is a heuristic in which each step moves the problem solver closer to the final goal.

Another heuristic is the creation of sub goals-intermediate, more manageable goals that may make it easier to reach the final goal.

Means-end analysis, a heuristic that combines hill climbing and sub goals, aims to reduce the discrepancy between the current situation and the desired goal at a number of intermediate points.

Working backward involves working from the desired goal back to the given conditions.

Effective problem solving is tied to many factors, including the right level of motivation or emotion. Too little emotion does not motivate, and too much may hinder the process of solution. Fixation is the inability to break out of a particular mindset. We call this factor that can help or hinder problem solving a set, the tendency to perceive and to approach problems in certain ways. Sets enable us to draw on past experience to solve a present problem, but a strong set can also interfere with ability to use new and different approaches to solving a problem. One set that can seriously hamper problem solving is functional fixedness, the tendency to perceive only a limited number of uses for an object. How many of you have used a credit card to scrape off your windshield?

Creativity is the ability to produce novel or unique ideas or objects which are also meaningful. For creativity to be meaningful, someone must be able to see the value, originality, or usefulness of the accomplishment. Visual imagery, ideational fluency, flexibility of thought, and originality combine to make up creative thinking. Visual imagery occurs when we see things in our "mind's eye." Highly creative people may come up with many ideas for a problem. We call this ideational fluency. If we have the ability to generate many different categories of ideas besides the obvious, we are said to possess flexibility of thought.

Creative people are often perceived as more intelligent. However, creative people are problem finders as well as problem solvers. Social psychologist Graham Wallas identified four stages of creative problem solving:

Preparation is discovering and defining a problem, then attempting to solve it.

Incubation describes putting the problem aside for a while and working on something else.

Insight describes the Eureka or insight solution moment when a solution comes immediately to mind.

Elaboration-verification is the solution even though it may still need to be confirmed.

The relationship between intelligence and creativity is not as simple as it seems. Some recent research has found that IQ and creativity are not strongly related. The one important trait commonly found in highly creative persons is openness to experience. Creative people tend to enjoy and seek out new experiences, new places, and new ideas.

To return to the session, close this window or tab.